The Latin Monetary Union

Origins of the Latin Monetary Union

The Latin Monetary Union was formed on December 23, 1865. It consisted of France, Belgium, Switzerland, and Italy. These four founding states agreed to mint their coins according to French standards, which Napoleon Bonaparte introduced in 1803. The standard dictated that while each nation would be allowed to mint its own currency (French Francs, Italian Lira, and so on), this currency had to follow a specific set of guidelines. The coins issued had to be silver or gold, a system known as bimetallism. These coins could then be exchanged at a rate of 15.5 silver coins to 1 gold.

These specifications were agreed to in order to ease trade and the flow of goods between the member states. A merchant in Switzerland could sell his goods in Belgium and get paid in Belgian Francs, knowing that the Belgian Franc contained the same amount of precious metals as the Swiss Franc. Back in Switzerland, this merchant could then exchange his Belgian Francs for Swiss Francs at face value, effectively eliminating the risk of currency fluctuations.

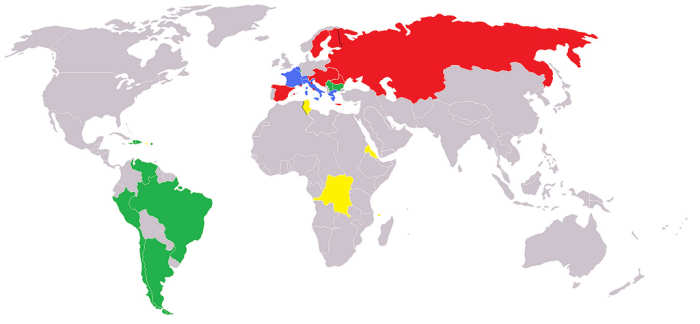

The success of the Union meant that, almost instantaneously, other nations either petitioned to join or attempted to standardize their currencies to match the Latin Monetary Union model. Greece was the first outside nation to join in 1867, while the ranks swelled even further during the 1870s and 1880s. Countries as far afield as Venezuela and Colombia joined in, while others, such as Austria-Hungary, which rejected the concept of bimetallism, standardized some of their coinage in order to smooth trade with the new currency bloc.

The Concept of Bimetallism

As mentioned above, the Latin Monetary Union was founded on the concept of bimetallism. Throughout history, coinage was minted out of a number of precious and nonprecious metals, like gold, silver, and copper. The value of the coin was essentially the value of the metal inside of it, and this allowed for some standardization of value as merchants would be able to determine how many goods it could purchase by analyzing the weight and metal content.

The concept of bimetallism takes this idea a step further by legislating that all official coins issued could be converted into either gold or silver. The exchange rate between the two types of coins would be fixed, guaranteeing price stability and ease when it came to exchanging currencies from different nations.

Although the concept seemed effective at first glance, a number of issues eventually grew to undermine the bi-metal system of currency issuance. The first weakness of the system was that gold and silver were not finite resources, in the sense that as new gold and silver mines were discovered, the increase of the precious metals on the open market would put pressure on the fixed exchange rate of the system. The second weakness was the fact that, as nations have often done before, the coins could be debased, meaning that one nation could mint a coin with a slightly lesser amount of gold, exchange it for another nation's currency, and pocket the difference as profit.

Struggles and Downfall

While The Latin Monetary Union grew to encompass countries as far afield as South America and the Dutch East Indies in Asia, it was ultimately doomed to fail. In the first decade or so, the Latin Monetary Union helped to bring in stability to exchange rates, and allowed for an easier flow of goods between states. Price stability meant that inflation was low, and trade flows increased. However, the design of the system itself meant that failure was almost certainly inevitable.

The first flaw in the system was the ability of individual states to mint their own coins. This enabled states to debase their currency relative to the other members, meaning that they could include less precious metals in their currency and exchange it for the currency of their fellow members, resulting in a profit for them. The first such instance of currency debasement happened almost instantly after the Latin Monetary Union was formed. in 1866, the Papal States, with France's blessing, began to mint coins with lower silver content.

When word got out, the debased currency started to crowd out the proper coins, as people traded in the cheaper silver coinage and kept the proper stuff for themselves. By 1870, the Papal States were ejected from the Latin Monetary Union, and their coinage was no longer exchanged according to the old standard.

The second blow came in 1873 when the price of silver fell so much that an enterprising person could profit from buying silver at open market rates and exchanging the silver for gold at the fixed rate of 15.5-1, selling the gold and repeating the process as long as possible. In 1874, the ability to convert silver to gold at official rates was suspended, and by 1878, silver was no longer being minted as coinage. This effectively moved the Latin Monetary Union onto the gold standard, whereby gold would be the ultimate guarantor of a currency's value.

After the conversion to the gold standard, the Latin Monetary Union experienced two decades of relatively prosperous economic growth. The next shocks came in 1896 and 1898 when massive gold deposits were discovered in the Klondike and South Africa. This influx of new gold threatened the stability of exchange rates and resulted in a readjustment to the value of the currency bloc.

The death blow to the Union came in 1914, as World War One broke out and the members of the Latin Monetary Union suspended the open conversion of money to gold, in effect abrogating the gold standard. Although the Latin Monetary Union existed on paper until 1927, it was effectively ended by the calamity of the First World War.

Modern-Day Euro Currency

While ultimately unsuccessful, the Latin Monetary Union holds a number of lessons for the present day. The ideals behind it, such as price stability, ease of trade, and better economic relations, were admirable and are, to this day, things that different states throughout the world pursue. The modern-day Euro currency, uniting states in the European Union and serving as a backstop for a number of other currencies, is a reincarnation of the concept of the European monetary union.

The gold standard was ultimately abandoned in 1971 by the United States of America, being the last vestige of the ideas that created the Latin Monetary Union. Today, the Euro is probably the closest approximation of the Latin Monetary Union, although it is considerably different than its predecessor.

First, the Euro is not backed by the physical value of precious metals but by the trust placed in the European Central Bank to maintain the value of the currency and ensure price stability. Second, the Euro is produced by one supranational body (The European Central Bank), meaning that no single state can "debase" its currency by printing more and more Euro banknotes and releasing them into circulation. While budgets are controlled by individual nations, the currency is controlled by a committee representing all the members, making the Euro-zone a more economically integrated bloc than the Latin Monetary Union.

Although relatively short-lived, the Latin Monetary Union laid the basis for further cooperation between European states. Integrating and simplifying trade between countries allowed for the development of economic and social links between disparate people. Although these links were challenged by wars and other strife, they ultimately blossomed into the modern European Union, which has been one of the longest and most prosperous periods of peace on the European continent.

Related Articles

- Functions and Responsibilities of the Central Bank and Commercial Banks

The functions of a central bank include formulating and implementing monetary policy. The commercial banks are the financial intermediaries between savers and investors as both are supply side of the money market. - Why Modern Monetary Theory Will Change the World

Learn about how the government can never go broke, taxes don't fund federal spending, the national debt isn't a debt, a budget surplus is bad, and money creation doesn't cause inflation. - Functions of Money in the Modern Economic System

The modern economy cannot work without money. Money is a medium of exchange, a measure of value, a store of value, and a standard of deferred payments.